Any time of year, visitors can take the Fairbank Driving Tour of Sculpture in the comfort of their vehicles and at their own speed.

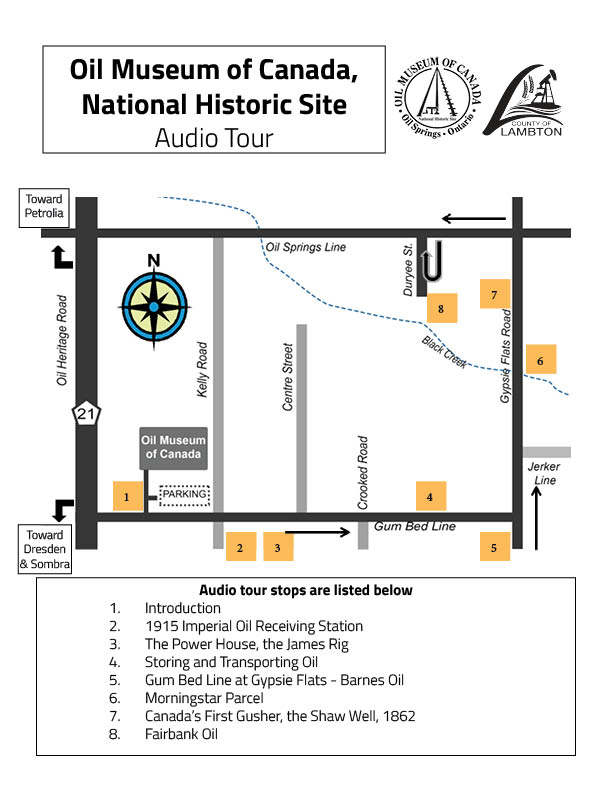

Before beginning the driving tour, it’s a good idea to first visit the Oil Museum of Canada in Oil Springs to get an overview of the oil history. A new system for the Audio Driving Tour delivers the narrative to your vehicle through your cell phone. The app for it is included in admission to the Oil Museum of Canada and it provides any help you may need with it. The great thing is that it also provides video clips, historic photos and extra info. You can take the driving tour at your own pace.

Sculptures on the tour visually tell the story of how the Lambton County oilmen produced and shipped the crude through many earlier decades. They depict men as they worked and they bring the past to life. Each sculpture is modelled after a real person and they are grouped like actors in a play. Together they make vignettes of men performing specific tasks.

The setting is the authentic oil field that still uses the technology of the 1860s. The “metal men” and six life-sized horses are the surprising folk art creations of Murray Watson, who owns and operates Watson Welding in Watford, Ontario.

Along the tour, you can hop out of your car and check out exhibits and the barn mural. You may want to bring a camera too.