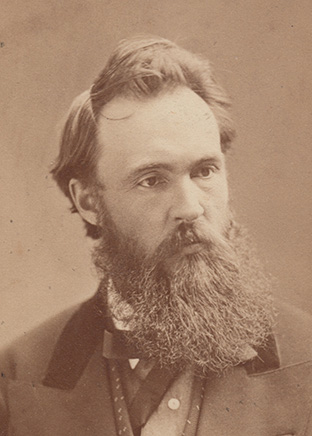

John Henry Fairbank 1831-1914

John Henry Fairbank is the man who began Fairbank Oil in the Great Swamp of Enniskillen of 1861. The place was Oil Springs, Ontario. It was here, just three years earlier, that the modern oil industry was born when James Miller Williams dug for oil, refined it and marketed his amazing oil for lamps. J.H. arrived as a 29-year old surveyor, supporting a wife and two young children who remained on their hardscrabble farm in Niagara Falls, Ontario.

When he died 54 years later, at the age of 83, J.H. had risen from a cash-strapped oil pioneer to a statesman presiding over a business empire employing more than 400 in nearby Petrolia. By 1900, he was the largest oil producer in Canada, pumping 24,000 barrels a year from his oil fields in Oil Springs and Petrolia. His home was the largest mansion in Lambton County. Its lush flower garden, ballroom, spacious rooms and fine furnishings, made an invitation to the Fairbank home an enviable coup.

“Oil magnate, banker, hardware dealer, wagon builder and sometime member of Canadian Parliament, in his own way, he achieved a pre-eminence in the Petrolia area parallel to that of a Carnegie or an Eaton,” wrote historian Edward Phelps.

Arriving in Oil Springs – 1861

Born in Rouse’s Point, New York, he showed a degree of pluck when he moved to Canada at the age of 22 to better his fortunes. He landed in Niagara Falls, Ontario and wed Canadian Edna Crysler two years later. They tried hard to farm but were finding there was little money in it. He had trained as a surveyor and it was a surveying job that first brought him to Oil Springs in March 1861.

Surrounded by hundreds of men all digging for oil, J.H. was soon infected with oil fever. In July, he leased a half-acre lot and christened his well Old Fairbank. His wife thought he had taken leave of his senses and begged him to come home.

Still in Oil Springs two years later, he was bothered by the expense of having a steam engine for each well. His solution was to devise the jerker line system – a “jerking” series of wooden rods close to the ground to transfer the power of one engine to multiple wells. It worked so well that this method was adopted throughout the district.

Heading For Petrolia – 1865

Oil Springs was in the full throes of the oil rush by 1865. The population ballooned to 4,000, hotels sprang up, and the oil field was a frenzy of activity. But J.H. quietly noticed his oil production was dropping. He sold his well for a princely sum and headed 12 kilometres north to Petrolia where small amounts of oil were being pumped.

His first order of business was to buy a small dry goods store there from S.H. Smallman. (Later it would become VanTuyl and Fairbank Hardware) Then, with his oil money he purchased a good deal of land at low prices. By November of 1865, he built a decent wooden house, subdivided lots of property and made a sizeable profit. All this was in place one year before the King Well discovery sparked a Petrolia oil boom that would stretch over four decades. And just as Petrolia boomed, the Oil Springs boom ended, almost overnight.

The Early Boom Years – 1866 – 1880

Though the oil business was still in its infancy in 1865, the pace of developments would be fast and furious. He built Fairbank Hall for meetings in 1866. In 1869, J.H. and his partner L.B. Vaughn created Petrolia’s first bank, which became known as The Little Red Bank. (The building was hauled from Oil Springs and today is Petrolia’s oldest building.)

By the mid 1870s, J.H. and other oil producers formed their own refinery, Home Oil, to combat the growing power of oil refiners. A sizeable operation, it refined 3,000 barrels a week. J.H. would be the president and general manager for eight years. He had another refinery too, Fairbank, Rogers and Company.

For his rapidly growing store, he took Captain Benjamin VanTuyl as his partner in 1874 and renamed it the VanTuyl and Fairbank Hardware. It became the largest hardware store west of Toronto. As well, J.H. became three terms as chief of the Petrolia Fire Brigade, an important job when the entire town was so flammable. It was a job he would take pride in for 30 years.

Producing oil remained his first priority though his holdings grew to include farmland, forests and real estate. In 1877, the Mutual Oil Association formed, it would be the first attempt to unite oil producers and regulate prices.

The Height of Boom Years – 1880 – 1890

By 1880, J.H. was nearly 50 years of age. There were nine refineries in Petrolia and Jacob Englehart’s newly built Silver Star Refinery was the biggest in the world. Hailed as the most sophisticated anywhere, it was processing 75,000 barrels at a time. Englehart had joined a group of London refiners and they formed Imperial Oil in April 1880. Imperial Oil took over the Silver Star Refinery in 1883. Resisting the clout of Imperial Oil was impossible and not surprisingly, Home Oil and the Fairbank Rogers and Company refineries were sold.

Once again, as the Petrolia boom heightened, J.H. was looking ahead. Looking to the long-term, he saw agriculture, not oil, as the future. In 1882, he opened Crown Savings and Loan to primarily grant mortgages to farmers. He retained the presidency of this bank for 30 years.

Oil production remained his first love and he was keenly interested to learn that Oil Springs had a second oil boom in 1881 thanks to deeper drilling. In 1882, J.H. bought a two-thirds interest of the Shannon property in Oil Springs, an oil field that had been pumping since 1861. In another eight years, he bought the remaining third. Later he bought an adjacent property and Fairbank Oil had reached 160 acres.

It was in 1882 when J.H. was elected Liberal Member of Parliament for East Lambton, a post he would keep until the 1887 election. This was not his first foray into politics. Earlier he had been elected reeve for three terms.

Dividing his time between Ottawa and Petrolia, J.H. became president of the Petrolia Oil Exchange in 1884. Meeting at the Little Red Bank, oil producers and refiners set the price of oil.

These were heady days in Petrolia. The town of wooden shanties was being transformed with stately brick Victorian buildings that spoke of permanence and prosperity.

The 1890s – The Tipping Point

Progress was continuing at a steady clip in Petrolia. In 1891, J.H. had completed his elegant mansion. It was also the year he bought Stevenson Boiler Works at a sheriff’s auction. It was a significant industry, making more than 90 per cent of all the boilers, tanks and stills used in producing and refining oil in Canada. Taking a keen interest in the boiler works, J.H. had it refitted and it continued as a profitable business.

By 1897, the population of Petrolia had soared to a new peak of almost 5,000. That’s when the first major blow hit the town. The American juggernaut, Standard Oil, headed by J.D. Rockefeller, began its takeover of Imperial Oil setting up Sarnia, not Petrolia, as its base.

The final deathblow came in the summer of 1898, when Standard Oil took over the Bushnell refinery in Sarnia and bought out Imperial Oil. All Imperial Oil operations in Petrolia shut down. The headquarters moved to Sarnia. And the town’s population plummeted by 1,000 people. At the same time, Petrolia’s steady flow of oil began to peter out.

One Era Ends, Another Begins – 1900 – 1914

The town was clearly jolted when Imperial Oil left, but within a few years there was renewed optimism. By 1901, Canadian Oil built a refinery in Petrolia. J.H. continued to invest in oil, and in 1905 he installed a new $14,000 rig in Oil Springs. Petrolia was determined to diversify and thrive.

The Petrolia Wagon Works started up in 1901 and produced 250 wagons in its first year. Mired with financial problems, J.H. agreed in 1908 to back its loans. Things did not improve and J.H. desperately tried to sell it. To compound woes for the wagon works, the first automobiles were appearing in the area.

As fate would have it, J.H. would not live to see the enormous implications of backing the wagon works loan. In 1920, six years after his death, the Wagon Works was bankrupt. The bank called the loan and the Fairbank family lost a third of their fortune.

In 1912, with declining health, J.H. had passed all his business dealings to his 56-year old son, (Major) Charles Oliver Fairbank. When J.H. died in February 1914, Petrolia had the biggest funeral in its history.

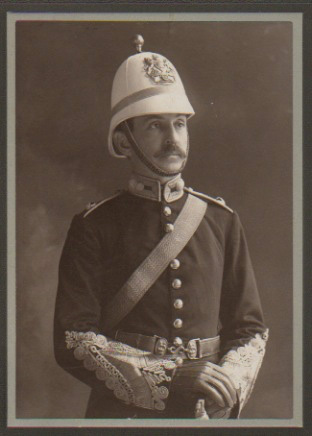

Major Charles Oliver Fairbank 1858 -1925

Charles Oliver Fairbank was 56 years old in 1912, when his father, John Henry Fairbank, put him in charge of all his business dealings. Though J.H. would live for another two years, his health was failing. Charles and his family moved into J.H.’s mansion to provide care. Charles, J.H. knew, was more than capable of taking the helm.

The father and son were uncommonly close throughout their lives and their bonding began when Charles was very young. They even shared the exact same birthday, July 21. For reasons unknown, at the age of four, Charles came to live with his father in his Oil Springs log shanty. Henry, the older brother of Charles, remained on the farm in Niagara Falls, Ontario with their mother, Edna. The family would not be fully reunited until four years later in Petrolia.

Charles grew up in the oil rush of Oil Springs and Petrolia, and through osmosis and his father, he learned a great deal about oil. As a young man, however, it appeared his destiny would be elsewhere. He studied at Helmuth College in London, Ontario and then, to his father’s delight, he enrolled in the newly established Royal Canadian Military College in Kingston. He was in its very first graduating class and emerged as a lieutenant. Afterwards, he took more military training in England.

His life was undoubtedly altered by the sudden death of his older brother, Henry, in 1881at the age of 24. Charles then became J.H. and Edna’s only son. Edna had also given birth to four younger children. The only daughter was May, 11 years younger than Charles. The three children died as infants or toddlers during their early years in Petrolia.

Charles went on to receive a medical degree at Columbia University in New York in 1891. In those days, a university education was a very rare thing. Because of his short stature, he became affectionately known as “The Little Doctor” yet he never made medicine his full-time profession.

He returned to Petrolia to work in the oil business. He and his business partner, Frank Carmen, developed new oil in Bothwell, 30 kilometres southeast of Petrolia. It was there he met his wife, Clara Sussex, and they went on to have four sons (John, Charles, Henry and Robert). To this day, the Bothwell rig’s steam engine of 1907 bears the initials of the two men.

In 1908, Charles and Carmen bought land in Elk Hills from the state of California and leased it to Standard Oil. Much later, in 1919, it was producing a great amount of oil and the U.S. government reclaimed the land. (Decades later, Charles’ son, Robert fought the ownership case in court for years but was unsuccessful.)

By 1912, he was immersed in his father’s business dealings in Petrolia and Oil Springs yet still managed to pursue his own business interests.

The year 1914 ushered in dramatic changes for Charles. J.H. died on Feb. 10 at the age of 83. With the death of his father, Charles lost a lifelong friend and mentor. Just one month after his death, Charles struck Canada’s first gas gusher by drilling deep in the Fairbank Oil land in Oil Springs. It grew to produce 11 million cubic feet daily with 830 pounds of pressure and was piped to Petrolia. Two months later, the gas was played out.

By August, World War One erupted. Overnight Charles resumed his military career. He was 58 years old and began by recruiting for the 70th Battalion. Family photos show the uniformed troops assembled in front of the Fairbank mansion with three-pole oil derricks in the background. Despite his age, Charles fought in the trenches at The Battle of the Somme and became a major. His diaries of the times tell of horrific carnage and also the wonder of seeing his first “aeroplane”.

Like his father, he was interested in politics and unsuccessfully ran as the Liberal MP in 1911. Charles did, however, serve as warden, reeve and became mayor of Petrolia in 1919.

Charles presided over the family businesses in challenging times. In 1920, the Petrolia Wagon Works went bankrupt and the Fairbank family, which had guaranteed the loans, was forced to pay more than $200,000 to the bank, wiping out a sizeable portion of their wealth. The Petrolia oil was diminishing and the royalties from the Elk Hills oil stopped when the U.S. government took over the oil fields.

In 1925, Charles died of Bright’s Disease at the age of 66. Fairbank Oil and the family’s hardware store would be passed to his son, later known as Charles Sr.

Charles Oliver Fairbank Sr. 1904 -1982

Charles Oliver Fairbank II never intended to run Fairbank Oil and the VanTuyl and Fairbank Hardware, yet this is how his life unfolded.

When his father (Maj. Charles Fairbank) died in 1925, Charles was just 21. He was the second of four sons born to Charles and Clara Fairbank. The ownership of family enterprises was passed to Charles and his three brothers, his father’s sister May in California and her children. Each owned one-eighth of these businesses.

Like the generation before him, Charles’ older brother died unexpectedly young, making him the eldest child. His brother John Henry Fairbank II, died in 1927 at the age of 26.

Charles, like his father, received a good education, studying at Ridley College in St. Catharines, and later taking a degree in petroleum engineering at the University of California. He was on his way to an engineering job in South America in 1932 when his mother asked him to return to Petrolia. It would be temporary, just long enough to help sort out the family finances. This task fell to Charles possibly because he became the eldest son. His brother Henry was two years younger and his brother Robert was a full 11 years younger.

The family had lost a good deal of income as oil revenues in Lambton County declined. Then, the stock market crashed in 1929 and the Great Depression was deepening. His mother had sold the main street portion of the VanTuyl and Hardware Store and also the Bothwell oil properties shortly before Charles returned to Petrolia.

Charles expected to stay a year but became immersed in issues. The Crown Savings and Loan, which his grandfather began, merged with Industrial Mortgage and Trust Company. Also, it was officially announced in 1935 that the Fairbank family lost its title to the lucrative oil land of Elk Hills, California. Fairbank Oil Fields, in Oil Springs, limped along with low prices and the low profits divided among the extended family.

Like his father and grandfather, Charles entered the world of politics. His term as reeve of Petrolia from 1934 to 1938 became a springboard for becoming the provincial Liberal Member of Parliament (Liberal) from 1938 to 1942. While MPP, he helped local oil producers by introducing a bill that made it easier to lease land for oil rights. He was also able to commission surveys of the heritage oil wells of Lambton County.

In 1940, he married Jean Harwood, originally from Moosejaw, Saskatchewan and they later had two children, Charles Oliver Fairbank III and Sylvia. Charles also worked with his mother’s second husband, Leo Ranney, a very talented engineer and inventor who pioneered the horizontal drilling of oil wells. The Australian government sought Ranney’s advice for increasing oil production and in 1941, Charles and Ranney travelled to Australia together.

Very active in the Petrolia community, Charles was heavily involved in restoring Greenwood Park and repurposing both the Petrolia Wagon Works and the old Imperial Oil refinery site.

After his mother, Clara Fairbank Ranney, died in 1956, he had the unenviable task of trying to sell or find a new use the Fairbank mansion. Various attempts were made over the years. But the most daunting task was emptying the house. Nearly 100 years worth of Fairbank family papers, accounts, receipts, maps, diaries, letters, photographs and paraphernalia had been stuffed into the turret… and they needed to be organized.

Charles tried to tackle the job but it was overwhelming. Fortunately, the University of Western Ontario came to the rescue and assigned the monumental task to Edward Phelps, who was completing his Masters degree in Canadian history. Thanks to the doggedness of Phelps and the pack-rat tendencies of the Fairbank family, an enormous amount of history has been saved. He spread out the materials on the floor of the mansion ballroom. Phelps finished his master thesis on John Henry Fairbank in 1965 and 15 boxes were donated to the university.

Another major accomplishment by Charles was achieving sole ownership of Fairbank Oil. He was urged to do this by his son, Charlie, who had returned to the area and was interested in running the oil field. Becoming the sole owner was not an easy task. Over the generations, there were an ever-growing number of descendants from the California branch of the family. There were also some legal complications. Finally, in 1973, it was achieved. His son Charlie then bought the oil property and took over the mortgage.

Charles Sr. and his son Charlie were very close. Charles tended to the hardware store and Charlie took on the oil fields with zeal. Along with others, they worked together to establish the develop The Petrolia Discovery, a working oil field promoting oil history. They also worked together in the 1970s on restoring the derelict Victoria Hall. Later, they worked together in making the plans for a massive stained glass window at Christ Church (Anglican) that incorporates all of the area’s oil history. This window, by the now famous artist Christopher Wallis, has received Ontario heritage designation.

Charles Fairbank died in 1982, fondly remembered by the town as Mr. Petrolia. His son, Charlie, took on the ownership of the store and oil field.

Charles "Charlie" Oliver Fairbank 1941 -

At the age of 28, Charlie worked in the Fairbank oil field for the first time. He was shocked to find he instantly fell in love with it. This budding encounter that year would blossom into a life-long love affair and would reroute his life.

Raised in Petrolia and living in several cities and towns during his twenties, he told his father (Charles Sr.) in 1969, that he wanted to run Fairbank Oil Fields. His father plainly told him he could never make a reliable living at it. For decades, the price of oil was charted as one low flat line. It was 1969 and oil was $3.32 a barrel.

His father suggested he should find another way to earn a living. If Charlie really wanted to run the oil field later, at least he would have something solid to fall back on in hard times.

Charlie heeded his father’s advice and obtained a teaching degree from Queen’s University’s McArthur College. He added this to his biology degree from the University of Western Ontario in London and his year of studying history at Concordia University in Montreal. After teaching secondary school science in Waterford and Pickering, he had his permanent teaching degree by 1973. His promise to his father was fulfilled.

The Arab Oil Embargo & A New Era

Charlie’s timing was extraordinary. In August 1973, he returned to Oil Springs and on October 5, 1973 Syria and Egypt attacked Israel, igniting the Yom Kippur War. Canada, the U.S. and several other countries, supported Israel. In retaliation, the Arab exporting nations imposed an oil embargo on them. Oil prices quadrupled. Headlines screamed of an energy crisis.

At the time, Fairbank Oil consisted of 70 productive wells and 70 idle wells on 350 acres. Today, there are 350 producing wells on 600 acres and a field staff of six. After oil prices collapsed in half in 1986, Charlie bought adjacent oil fields as they became available. With these additional 250 acres, he believed Fairbank Oil would have greater economy of scale – more oil flowing from the extra 200 wells with little increase in operating costs. It was an intense decade of developing oil gathering systems, overhauling wells, clearing forest growth, excavating roads and extending electrical lines.

Reigning in the Ownership

Back in 1969, Charlie urged his father to gain sole ownership of Fairbank Oil. The meagre profits were diminished even more when shared with all the family descendants. It was also difficult to make decisions about the oil field when approval was needed from so many.

Over the decades, shares had been divided and subdivided through the generations of the family and there were also legal hurdles. It took Charles Sr. years of effort but in 1973, he succeeded. Charlie promptly bought the property from his father and took over the mortgage.

Charlie became the first Fairbank to live in Oil Springs and work daily in the oil field since the time of his great grandfather, John Henry Fairbank who left in 1865 for Petrolia.

Pumping Oil in the Oil Heritage District

Here in the Oil Heritage District, oil producers are called “strippers” or “marginal producers” because the days of prolific wells are in the distant past. Today, the marginal producers continue to coax the wells into producing about one-sixth of a barrel a day. For every three barrels of oil produced at Fairbank Oil, 50 barrels of salty water are produced and are sent to disposal wells.

The viability of the oil producers depends entirely on the world price of oil. Politics, wars, oil embargos, weather events and changes in technology affect supply and demand. Like farmers, the oil producers have no control over the selling price. And since these are marginal fields, they are unable to increase production. Oil producers can only try to control their costs.

A New Era of Interest in Oil Heritage

The running of Fairbank Oil is Charlie’s main occupation, but his life’s work is to gain recognition for the Oil Heritage District.

Starting in the 1990s, interest in the rich oil history of the area began to swell. Several projects were gaining the eye of the public. By chance, Dr. Emory Kemp of West Virginia University arrived in Oil Springs and wanted to learn more. He was then the university’s director for the Institute for the History of Technology and Industrial Archaeology. By the summer of 1999, he set up a six-week field school of university staff and his American students at Fairbank Oil.

When Dr. Kemp set up a second field school at Fairbank Oil in 2001, he had with him staff members of Parks Canada (which oversees National Historic sites) The Museum of Science and Technology in Ottawa and the University of Western Ontario.

Dr. Kemp publicly proclaimed Fairbank Oil and the surrounding area meet the criteria for becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Taking the Oil Story to the Public

For more than 20 years, Charlie and the late Robert Cochrane of Cairnlins Resources were tireless supporters of The Petrolia Discovery. They helped found this outdoor oil field museum in 1980, each became chairmen, and together they maintained the oil wells there every Saturday for more than two decades. They both retired from Discovery in 2003 to focus their energies on ambitious plans for Oil Spring’s 150th anniversary in 2008.

The 2008 celebrations commemorated James Miller Williams, who in 1858 gave birth to the modern oil industry when he dug a well in Oil Springs, and then produced, refined and marketed his oil.

Charlie was also able to attract the attention of heritage professionals. During 2008, two major conferences were held in Oil Springs: The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS); and a joint conference of the American-based Petroleum History Institute and Petroleum History Society in Canada. Robert Cochrane of Cairnlin Resources, along with Robert Tremain of Lambton County Museums and Charlie, helped organize these events that brought in historians and media from distant places.

These efforts also sparked the very thorough Lambton County study that created the Oil Heritage Conservation District Plan in 2010. Among the numerous endeavours to promote Lambton’s oil history, several books have been published. Charlie created a publishing enterprise and published the oil research by writers Patricia McGee (The Story of Fairbank Oil, 2004), Edward Phelps (Petrolia, Ontario-Canada, 150 Years 1854 -2004) and Dr. Emory Kemp (19th Century Petroleum Technology in North America, 2007).

Charlie has also been to be a valuable resource to other countless writers including Earle Gray (author of two books on the area: The Great Canadian Oil Patch, Second Edition, 2005; and Ontario’s Petroleum Legacy, 2007); Gary May (Hard Oiler! 1996, Groundbreaker, 2013) and Hope Morritt (Rivers of Oil, 1993).

Writers Earle Gray and William Marsden, both wrote extensively about Charlie in their final chapters. In Gray’s book, The Great Canadian Oil Patch, the writing is under the subheading The Oldest Survivor. In Marsden’s award winning Stupid to the Last Drop, the heading for the epilogue is To The Last Drop, In Which Charlie Fairbank Unveils the Future.

There have also been specialized books for industrial archaeologists and geologists such as Christopher Andreae’s book Lambton’s Industrial Heritage in 2000. This was also the year Robert Cochrane and Charlie penned the Oil Heritage Tour of Lambton County: The Birthplace of the Canadian Oil Industry. Earlier in 1989, Survivals, Aspects of Industrial Archaeology in Ontario was written by Dianne Newell and Ralph Greenhill. It contains several photos of Fairbank Oil equipment and Charlie furnished the authors will lots of detail.

Edward Burtynsky, the Canadian photographer who has won international acclaim for his large format industrial landscapes, had also taken an interest in Oil Springs. In his 2009 book Burtynsky Oil is an essay by Michael Mitchell who writes that Fairbank Oil stands in sharp contrast to massive stark oil operations elsewhere in the world. With its green countryside dotted with sheep Fairbank Oil sounds idyllic.

Charlie has appeared in numerous newspapers and magazines over the years and during the 2008 Oil Springs celebrations, he was front-page news for The Toronto Star.

Beyond the printed word, Charlie has been giving interviews on film. He has appeared on the History Channel, with the National Film Board, the Ontario Visual Heritage Project and even in Mike and Mike’s Excellent Adventure on Much Music.

He is also sought out as a lively speaker. He addressed an audience of more than 800 at the inaugural gathering of The Canadian Petroleum Hall of Fame in Leduc, Alberta and has given several substantive speeches to the Ontario Petroleum Institute. In 2009, he gave his first speech to an international audience when addressing The International Committee for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage (TICCIH) in Freiberg, Germany. In the following year, he spoke at The Canada Science and Technology Museum in Ottawa. Closer to home, he has given numerous colourful speeches for a wide spectrum of local organizations such as gathering of The Flying Farmers and the Red Hatters.

The speech with the most impact was delivered in October 2017 in Ottawa. The International Association for the Preservation Technology (APT) asked him to give a presentation at a conference jointly organized with National Trust, the umbrella group of all heritage in Canada. In the spring of 2018, APT published Charlie’s essay that was based on his speech. The Bulletin is read in 115 countries. Charlie won an APT award for the essay.

For friends or special interest groups, Charlie has given occasional private tours of Fairbank Oil. These are always informative with fun stories woven into them. One year at the Petrolia Fall Fair, a tour with Charlie, was put on auction as a fair fundraiser. A bidding war broke out and the gavel went down with the cry of “sold!” when it topped $300.

Awards & Recognition

In ways both great and small, Charlie’s efforts to gain recognition for oil heritage has been noted. In 1992, he received the Canada 125 medal and in 2002, he was presented with the medal for the Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee. He has received numerous awards, including the Ontario Lieutenant Governor’s Lifetime Achievement Award for Heritage in 2008 and the similarly named National Trust’s Lieutenant Governor’s Award for Life Achievement in 2013.

In 2008, the American-based Petroleum History Institute presented him with The Samuel T. Pees Keeper of the Flame Award, for maintaining the heritage of Fairbank Oil in its fourth generation. In 2008, he also received a lifetime achievement award from the Petroleum History Society in Alberta and in 2011 he was inducted to Canada’s Petroleum Hall of Fame.

Charlie is married to writer Patricia McGee and they have two sons, Charlie born in 1992, and Alex born in 1996.

In 2024, Charlie was honoured as a Heritage Champion by the County of Lambton and his wife, Pat McGee, also was named as a Heritage Champion. They have two sons, Charlie, born in 1992 and Alex, born in 1996.